- Keep your kidneys healthy by being “water wise.” This means drinking the right amount of water for you. A common misconception is that everyone should drink eight glasses of water per day, but since everyone is different, daily water needs will vary by person. How much water you need is based on differences in age, climate, exercise intensity, as well as states of pregnancy, breastfeeding, and illness.About 60-70% of your body weight is made up of water, and every part of your body needs it to function properly. Water helps the kidneys remove wastes from your blood in the form of urine. Water also helps keep your blood vessels open so that blood can travel freely to your kidneys, and deliver essential nutrients to them. But if you become dehydrated, then it is more difficult for this delivery system to work. Mild dehydration can make you feel tired, and can impair normal bodily functions. Severe dehydration can lead to kidney damage, so it is important to drink enough when you work or exercise very hard, and especially in warm and humid weather.

- Here are 6 tips to make sure you’re drinking enough water and to keep your kidneys healthy:

- Eight is great, but not set in stone. There is no hard and fast rule that everyone needs 8 glasses of water a day. This is just a general recommendation based on the fact that we continually lose water from our bodies, and that we need adequate water intake to survive and optimal amounts to thrive. The Institute of Medicine has estimated that men need approximately 13 cups (3 liters) of fluid daily, and that women need approximately 9 cups (2.2 liters) of fluid daily.

- Less is more if you have kidney failure (a.k.a. end stage kidney disease). When the kidneys fail, people don’t excrete enough water, if any at all. For those who are receiving dialysis treatment, water must actually be greatly restricted.

- It’s possible to drink too much water. Though it is not very common for this to happen in the average person, endurance athletes like marathoners may drink large amounts of water and thereby dilute the sodium level in their blood, resulting in a dangerous condition called hyponatremia.

- Your urine can reveal a lot. For the average person, “water wise” means drinking enough water or other healthy fluids, such as unsweetened juice or low fat milk to quench thirst and to keep your urine light yellow or colorless. When your urine is dark yellow, this indicates that you are dehydrated. You should be making about 1.5 liters of urine daily (about 6 cups).

- H2O helps prevent kidney stones and UTIs. Kidney stones and urinary tract infections (UTIs) are two common medical conditions that can hurt the kidneys, and for which good hydration is essential. Kidney stones form less easily when there is sufficient water available to prevent stone-forming crystals from sticking together. Water helps dissolve the antibiotics used to treat urinary tract infections, making them more effective. Drinking enough water also helps produce more urine, which helps to flush out infection-causing bacteria.

- Beware of pills and procedures. Drinking extra water with certain medications or before and after procedures with contrast dye may help prevent kidney damage. Read medication labels and ask questions before undergoing medical procedures involving contrast dyes. Always consult with your healthcare provider first though, especially if you are on a fluid restriction.

- You may know cranberries as a tasty and tart small red fruit with a history of consumption dating back to Native Americans and the earliest European settlers, but did you know that they are also good for your urinary tract and your kidneys? If you aren’t already eating cranberries, consider adding them to your grocery list. A fall favorite, cranberries have long been a holiday staple but as a result of their versatility they can be consumed dried, fresh, cooked and even as juice – it’s easy to find a “reason for every season” to incorporate cranberries into your diet throughout the year.Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are responsible for nearly 10 million doctor visits each year. A urinary tract infection is what happens when bacteria (germs) get into the urinary tract (including the bladder) and multiply. The result is redness, swelling and pain in the urinary tract. Most UTIs stay in the bladder, but if not treated quickly they can travel up the ureter and into the kidneys, causing a more serious and painful kidney infection called pyelonephritis.About 80 to 90 percent of UTIs are caused by a single type of bacteria, E. coli. These bacteria normally live in your intestines, but sometimes they get into the urinary tract and the kidneys. This is where incorporating cranberries into your diet becomes important. Cranberries contain compounds that can stop the bacteria from “sticking” to the urinary tract wall and studies in young women with frequent UTIs show that drinking a glass of cranberry juice each day may help reduce recurrent or repeat UTIs. Research also suggests a similar effect from the consumption of other cranberry products, including dried cranberries and dietary supplements. For those with diabetes or at-risk for diabetes, low-sugar cranberry products are available. Ask your treating clinician if increasing cranberry consumption in your diet is right for you.A serving of fresh cranberries is a good source of vitamin C and fiber, provides antioxidant polyphenols, and contains only 1 mg of sodium. Here are 6 tips from the National Kidney Foundation for incorporating cranberries into your diet.

- Add some crunch. Dried cranberries are a great snack choice (just watch out for added sugar). Enjoy them plain or consider adding them to homemade trail mix.

- Spruce up your salad. Fresh and dried cranberries can be easily tossed into salads for colorful and tasty burst of flavor.

- Keep it classic. Cranberry juice is a classic beverage and is an easy way to get your fill of cranberries. Just grab a glass!

- Some like it hot. Cranberry tea is a delicious way to drink cranberries during the cooler months.

- Bake a brunch spread. Fresh and dried cranberries make a great addition to oatmeal, muffins and other baked goods, adding texture and nutrients.

- Color your couscous. Add a pop of color, flavor and sweetness to your favorite couscous or pasta salad recipe. This makes for an easy and delicious dish to take to a pot-luck party!

For more information about UTIs, please visit the A-Z Guide and for some kidney-friendly cranberry recipes, visit the Kidney Kitchen.

Many of us don’t give much thought to our hardworking kidneys. The truth is 33% of adults in the United States are at risk for developing kidney disease.

The main risk factors of kidney disease are diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, a family history of kidney disease, and obesity.

Here are 7 Golden Rules of Prevention to lower your chances of getting kidney disease.

1. Get regular check-ups

2. Control Blood Pressure

3. Manage Blood Sugar

4. Eat a Healthy Diet

5. Exercise

6. Quit Smoking

7. Do not overuse pain medicines

Read Complete Article At: https://www.kidney.org/prevention/7-golden-rules-of-prevention

Kidney Diet Local Pdf : Click to download

Chronic kidney disease, also known as chronic renal disease or CKD, is a condition characterized by a gradual loss of kidney function over time.

Kidney disease facts:

- 37 million American adults have CKD, and millions of others are at increased risk

- Early detection can help prevent the progression of kidney disease to kidney failure

- Heart disease is the primary cause of death for all people with CKD

To read more facts about Chronic Kidney Disease Visit: https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/about-chronic-kidney-disease

Or see the table of contents below

Table of Contents

- Chronic kidney disease & COVID-19

- Kidney disease facts

- What are the main causes of chronic kidney disease?

- What are other conditions that affect the kidney?

- What are the risk factors of chronic kidney disease?

- What are the symptoms?

- What will happen if my doctor suspects chronic kidney disease?

- Additional tests

Dialysis is a treatment that does some of the things done by healthy kidneys. It is needed when your own kidneys can no longer take care of your body’s needs.

When is dialysis needed?

You need dialysis when you develop end stage kidney failure –usually by the time you lose about 85 to 90 percent of your kidney function and have a GFR of <15.

What does dialysis do?

When your kidneys fail, dialysis keeps your body in balance by:

- removing waste, salt and extra water to prevent them from building up in the body

- keeping a safe level of certain chemicals in your blood, such as potassium, sodium and bicarbonate

- helping to control blood pressure

To know more about What is dialysis visit: https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/dialysisinfo

Or see the table of contents below:

Table of Contents

- Dialysis & COVID-19

- When is dialysis needed?

- What does dialysis do?

- Is kidney failure permanent?

- Where is dialysis done?

- Are there different types of dialysis?

- What is hemodialysis?

- How long do hemodialysis treatments last?

- What is peritoneal dialysis and how does it work?

- What are the different kinds of peritoneal dialysis and how do they work?

- Will dialysis help cure the kidney disease?

- Is dialysis uncomfortable?

- How long has dialysis been available?

- How long can you live on dialysis?

- Is dialysis expensive?

- Do dialysis patients feel normal?

- Do dialysis patients have to control their diets?

- Can dialysis patients travel?

- Can dialysis patients continue to work?

Video

Medications That Can Cause Nephrotoxicity (Kidney Damage)

The kidney is a vital organ that performs several essential functions in the body, including detoxification (removing toxins from the blood) and maintaining homeostasis ( the body’s ability to maintain a stable, constant environment internally). Nephrotoxicity is a term used to describe a rapid deterioration in kidney function due to the toxic effects of chemicals or drugs (approximately 20% of nephrotoxicity is caused by drugs).

Please continue reading to learn more about nephrotoxicity and some medication classes that can cause kidney damage.

WHAT ARE ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY (ACUTE RENAL FAILURE) AND CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE?

Before we look at some of the medications that can cause kidney damage, let’s understand the different types of kidney dysfunction. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity can contribute to two types of kidney disease – acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Acute Renal Failure

Acute kidney injury (also referred to as acute renal failure) develops rapidly. It can range from minor to severe renal dysfunction requiring renal replacement therapy (dialysis). Doctors manage acute kidney injury by identifying and treating the underlying cause while minimizing associated complications. Acute kidney injury is usually reversible.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) develops gradually for months or even years. It is usually the result of a chronic condition such as diabetes or high blood pressure. Most patients with CKD don’t have any symptoms in the early stages, and the condition is typically discovered incidentally on routine testing for unrelated problems. Medical treatment can slow the progress of renal dysfunction. However, keep in mind that CKD is irreversible and eventually leads to end-stage renal disease with the need for dialysis or a kidney transplant.

Types of Kidney Damage

Doctors also use specific terms to describe where the damage has occurred in the kidney. For example, acute tubular necrosis refers to damage to the renal tubular cells; tubules are tiny ducts responsible for the reabsorption of water and other nutrients back to the blood. Glomerulonephritis refers to an inflammation of the kidneys’ glomeruli – the cluster of nerve endings or small blood vessels filtering the blood. Interstitial nephritis refers to an inflammation of the spaces between the tubules – it can be short-term (acute interstitial nephritis) or long-term (chronic interstitial nephritis).

Rhabdomyolysis

A potentially life-threatening condition called rhabdomyolysis warrants mention here. Rhabdomyolysis is a serious condition caused by muscle injury or muscle death. . As the muscle cells are broken down, a substance called myoglobin is released into the blood. Large quantities of myoglobin can damage the kidneys; this can lead to acute renal failure because the kidneys are unable to remove the waste material from the blood efficiently. Therefore, drugs that can cause rhabdomyolysis can indirectly lead to acute renal failure.

WHO IS AT RISK OF DRUG-INDUCED RENAL FAILURE?

Some people are at higher risk of drug-induced nephrotoxicity (kidney damage) than others. Patient-related risk factors include:

- Older age (over 60 years)

- Underlying renal insufficiency – reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and/or elevated serum creatinine (SCr) and/or blood urea nitrogen (BUN).

- Medical conditions such as intravascular volume depletion (seen in vomiting, diarrhea, and bleeding), diabetes, cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, liver dysfunction, electrolyte imbalances, and sepsis.

Drug-induced nephropathy (kidney dysfunction) also depends on drug-related risk factors. For example, some types of drug-induced kidney damage are dose-dependent. These predictable effects occur when a medication is given at high doses or for a longer duration. For instance, aminoglycoside antibiotics are known to cause nephrotoxicity at high doses. The other type of drug-associated renal dysfunction is unpredictable and unrelated to dose. For instance, proton pump inhibitors can cause interstitial nephritis, and there is no way to predict or prevent the damage.

In hospitalized patients, drug-induced kidney damage occurs due to concurrent use of more than one medication that can cause nephrotoxic acute renal failure and possible chronic renal failure without prompt discontinuation of the offending drugs. For example, patients treated with pain relievers (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications [NSAIDs]) and certain antibiotics are at considerably higher risk of drug-induced acute kidney injury. Both of these drugs can cause kidney damage, thus, decreasing kidney function over time. The risk of renal toxicity and hospital-acquired renal insufficiency can be lowered by minimizing exposure to multiple nephrotoxic drugs, in addition to assessing other risk factors such as age and other medical conditions.

WHICH MEDICATION IS MOST LIKELY TO CAUSE NEPHROTOXICITY?

Multiple medication classes can cause drug-induced kidney disease. Some of them are described below. This article aims to familiarize you with different nephrotoxic drug classes. Though different drug classes can cause specific types of kidney injury, do not get overwhelmed with the medical terminology. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist if you have more questions about the different types of kidney injury.

Pain Relievers

Pain medications such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) and aspirin can cause chronic interstitial nephritis. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) and naproxen sodium (Aleve) are some of the most common culprits in causing drug-induced nephrotoxicity. NSAIDs can lead to acute interstitial nephritis, chronic interstitial nephritis, and glomerulonephritis. Long-term use of these medications can lead to chronic kidney disease.

Antidepressants and Mood Stabilizers

Certain antidepressants like fluoxetine (Prozac), amitriptyline (Elavil), and doxepin (Zonalon) can cause rhabdomyolysis, leading to acute kidney injury. The mood stabilizer lithium used to treat bipolar disorder can also cause rhabdomyolysis, then kidney injury–specifically chronic interstitial nephritis and glomerulonephritis.

Antihistamines

Medications such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and doxylamine (Unisom) can contribute to rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury.

Antimicrobials

Antimicrobials such as aminoglycosides, antifungals (amphotericin B), beta-lactams (cephalosporins, penicillins), quinolones (ciprofloxacin), rifampin (Rifadin), and vancomycin (Vancocin) can lead to drug-induced acute renal failure.

Antiviral medications such as acyclovir (Zovirax), Foscarnet (Foscavir), and ganciclovir (Cytovene) are also known to cause drug-induced nephrotoxicity.

Pentamidine (Pentam), a broad-spectrum antimicrobial used to treat parasitic infections, may cause acute tubular injury.

Statins

Rarely, cholesterol-lowering medications called statins (simvastatin (Zocor) and atorvastatin (Lipitor) can cause rhabdomyolysis, resulting in acute renal failure.

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors (drugs that reduce stomach acid production), such as lansoprazole (Prevacid), pantoprazole (Protonix), and omeprazole (Prilosec), can cause acute interstitial nephritis.

Cardiovascular Medications

Medications used to treat cardiovascular diseases, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and diuretics (water pills) such as triamterene (Dyrenium), can cause drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Platelet inhibitors, such as clopidogrel (Plavix) and ticlopidine (Ticlid), have been shown to rarely cause drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy (small clots that lead to red blood cell damage).

Antiretrovirals

Antiretroviral drugs used to treat HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, cytomegalovirus infection can cause tubular cell toxicity and acute interstitial nephritis. Examples include adefovir (Hepsera), tenofovir (Viread), cidofovir (Vistide), and indinavir (Crixivan).

Immunosuppressants

Calcineurin inhibitors that prevent organ rejection after transplant can cause drug-induced nephropathy. Examples include tacrolimus (Prograf) and cyclosporine (Neoral).

Chemotherapy Medications

Chemotherapeutic agents such as carmustine (Gliadel), cisplatin (Platinol), interferon-alfa (Intron A), methotrexate, and mitomycin-C (Mutamycin) can cause drug-induced kidney disease.

Contrast-Induced Nephropathy

Exposure to intravenous contrast agents (dyes) used during medical imaging such as CT, MRI, and X-ray can lead to tubular cell toxicity and acute tubular necrosis. This type of renal injury is called contrast-induced nephropathy.

Drugs of Abuse

Heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, and ketamine (Ketalar) can cause drug-induced rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure.

Herbal Products

Certain Chinese herbs such as aristolochic acid have been linked to drug-induced nephrotoxicity, specifically chronic interstitial nephritis.

The above list is by no means a comprehensive list of medications that can cause drug-induced nephrotoxicity. If you are at high risk of drug-induced nephrotoxicity due to age, underlying renal dysfunction, or comorbidities such as diabetes, you should talk to your doctor about assessing your baseline renal function before starting any new medication that can potentially cause kidney damage. Also, ask questions about nephrotoxic drug combinations (taking more than one medication that can cause renal injury) to find out if your current medications put you at higher risk for kidney injury.

Keep all your doctor and blood test appointments. Your doctor will want to monitor renal function while taking drugs associated with nephrotoxicity.

Drug-induced nephrotoxicity is usually reversible with early detection. Doctors can treat drug-induced nephrotoxicity by discontinuing the culprit medication, replacing fluids, and treating kidney inflammation.

References:

Potassium and your CKD Diet

- Potassium is a mineral found in many of the foods you eat. It plays a role in keeping your heartbeat regular and your muscles working right. It is the job of healthy kidneys to keep the right amount of potassium in your body. However, when your kidneys are not healthy, you often need to limit certain foods that can increase the potassium in your blood to a dangerous level. You may feel some weakness, numbness and tingling if your potassium is at a high level. If your potassium becomes too high, it can cause an irregular heartbeat or a heart attack.

What is a safe level of potassium in my blood?

Ask your doctor or dietitian about your monthly blood potassium level and enter it here:

If it is 3.5-5.0………………………You are in the SAFE zone

If it is 5.1-6.0………………………You are in the CAUTION zone

If it is higher than 6.0……………..You are in the DANGER zone

How can I keep my potassium level from getting too high?

- You should limit foods that are high in potassium. Your renal dietitian will help you plan your diet so you are getting the right amount of potassium.

- Eat a variety of foods but in moderation.

- If you want to include some high potassium vegetable in your diet, leach them before using. Leaching is a process by which some potassium can be pulled out of the vegetable. Instructions for leaching selected high potassium vegetables can be found at the end of this fact sheet. Check with your dietitian on the amount of leached high potassium vegetables that can be safely included in your diet.

- Do not drink or use the liquid from canned fruits and vegetables, or the juices from cooked meat.

- Remember that almost all foods have some potassium. The size of the serving is very important. A large amount of a low potassium food can turn into a high- potassium food.

- If you are on dialysis, be sure to get all the treatment or exchanges prescribed to you.

What is a normal amount of potassium intake per day for the average healthy individual?

- A normal amount of potassium in a typical diet of a healthy American is about 3500 to 4500 milligrams per day. A potassium restricted diet is typically about 2000 milligrams per day. Your physician or dietitian will advise you as to the specific level of restriction you need based on your individual health. A kidney dietitian is trained to help you make modifications to you diet in order to prevent complications for kidney disease.

What foods are high in potassium (greater than 200 milligrams per portion)?

The following table lists foods that are high in potassium. The portion size is ½ cup unless otherwise stated. Please be sure to check portion sizes. While all the foods on this list are high in potassium, some are higher than others.

| High-Potassium Foods | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fruits | Vegetables | Other Foods |

| Apricot, raw (2 medium) dried (5 halves) |

Acorn Squash | Bran/Bran products |

| Avocado (¼ whole) | Artichoke | Chocolate (1.5-2 ounces) |

| Banana (½ whole) | Bamboo Shoots | Granola |

| Cantaloupe | Baked Beans | Milk, all types (1 cup) |

| Dates (5 whole) | Butternut Squash | Molasses (1 Tablespoon) |

| Dried fruits | Refried Beans | Nutritional Supplements: Use only under the direction of your doctor or dietitian. |

| Figs, dried | Beets, fresh then boiled | |

| Grapefruit Juice | Black Beans | |

| Honeydew | Broccoli, cooked | Nuts and Seeds (1 ounce) |

| Kiwi (1 medium) | Brussels Sprouts | Peanut Butter (2 tbs.) |

| Mango(1 medium) | Chinese Cabbage | Salt Substitutes/Lite Salt |

| Nectarine(1 medium) | Carrots, raw | Salt Free Broth |

| Orange(1 medium) | Dried Beans and Peas | Yogurt |

| Orange Juice | Greens, except Kale | Snuff/Chewing Tobacco |

| Papaya (½ whole) | Hubbard Squash | |

| Pomegranate (1 whole) | Kohlrabi | |

| Pomegranate Juice | Lentils | |

| Prunes | Legumes | |

| Prune Juice | White Mushrooms, cooked (½ cup) | |

| Raisins | Okra | |

| Parsnips | ||

| Potatoes, white and sweet | ||

| Pumpkin | ||

| Rutabagas | ||

| Spinach, cooked | ||

| Tomatoes/Tomato products | ||

| Vegetable Juices | ||

What foods are low in potassium?

The following table list foods which are low in potassium. A portion is ½ cup unless otherwise noted. Eating more than 1 portion can make a lower potassium food into a higher potassium food.

| Low-Potassium Foods | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fruits | Vegetables | Other Foods |

| Apple (1 medium) | Alfalfa sprouts | Rice |

| Apple Juice | Asparagus (6 spears raw) | Noodles |

| Applesauce | Beans, green or wax Broccoli (raw or cooked from frozen) |

Pasta |

| Apricots, canned in juice | Cabbage, green and red Carrots, cooked |

Bread and bread products (Not Whole Grains) |

| Blackberries | Cauliflower | Cake: angel, yellow |

| Blueberries | Celery (1 stalk) | Coffee: limit to 8 ounces |

| Cherries | Corn, fresh (½ ear) frozen (½ cup) | Pies without chocolate or high potassium fruit |

| Cranberries | Cucumber | Cookies without nuts or chocolate |

| Fruit Cocktail | Eggplant | Tea: limit to 16 ounces |

| Grapes | Kale | |

| Grape Juice | Lettuce | |

| Grapefruit (½ whole) | Mixed Vegetables | |

| Mandarin Oranges | White Mushrooms, raw (½ cup) | |

| Peaches, fresh (1 small) canned (½ cup) |

Onions | |

| Pears, fresh (1 small) canned (½ cup) |

Parsley | |

| Pineapple | Peas, green | |

| Pineapple Juice | Peppers | |

| Plums (1 whole) | Radish | |

| Raspberries | Rhubarb | |

| Strawberries | Water Chestnuts, canned | |

| Tangerine (1 whole) | Watercress | |

| Watermelon (limit to 1 cup) | Yellow Squash | |

| Zucchini Squash | ||

How do I get some of the potassium out of my favorite high-potassium vegetables?

The process of leaching will help pull potassium out of some high-potassium vegetables. It is important to remember that leaching will not pull all of the potassium out of the vegetable. You must still limit the amount of leached high-potassium vegetables you eat. Ask your dietitian about the amount of leached vegetables that you can safely have in your diet.

How to leach vegetables.

For Potatoes, Sweet Potatoes, Carrots, Beets, Winter Squash, and Rutabagas:

- Peel and place the vegetable in cold water so they won’t darken.

- Slice vegetable 1/8 inch thick.

- Rinse in warm water for a few seconds.

- Soak for a minimum of two hours in warm water. Use ten times the amount of water to the amount of vegetables. If soaking longer, change the water every four hours.

- Rinse under warm water again for a few seconds.

- Cook vegetable with five times the amount of water to the amount of vegetable.

Read more about Potassium and Your CKD Diet.

References:

Bowes & Church Food Values of Portions Commonly Used, 17th Ed., Pennington, JA, Lippincott, 1998.

Diet Guide for Patients with Kidney Disease, Renal Interest Group-Kansas City Dietetic Association, 1990.

-

Table of Contents

- What is potassium and why is it important to you?

- What is a safe level of potassium in my blood?

- How can I keep my potassium level from getting too high?

- What is a normal amount of potassium intake per day for the average healthy individual?

- What foods are high in potassium (greater than 200 milligrams per portion)?

- What foods are low in potassium?

- How do I get some of the potassium out of my favorite high-potassium vegetables?

Kidney Transplants

What is a “preemptive” or “early” transplant?

Getting a transplant before you need to start dialysis is called a preemptive transplant. It allows you to avoid dialysis altogether. Getting a transplant not long after kidneys fail (but with some time on dialysis) is referred to as an early transplant. Both have benefits. Some research shows that a pre-emptive or early transplant, with little or no time spent on dialysis, can lead to better long-term health. It may also allow you to keep working, save time and money, and have a better quality of life.

What if I’m older or have other health problems?

-

In many cases, people who are older or have other health conditions like diabetes can still have successful kidney transplants. Careful evaluation is needed to understand and deal with any special risks. You may be asked to do some things that can lessen certain risks and improve the chances of a successful transplant. For example, you may be asked to lose weight or quit smoking.If you have diabetes, you may also be able to have a pancreas transplant. Ask your healthcare professional about getting a pancreas transplant along with a kidney transplant.

How will I pay for a transplant?

Medicare covers about 80% of the costs associated with an evaluation, transplant operation, follow-up care, and anti-rejection medicines. Private insurers and state programs may cover some costs as well. However, your post-transplant expenses may only be covered for a limited number of years. It’s important to discuss coverage with your social worker, who can answer your questions or direct you to others who can help. Click here to learn more about insurance and transplant.

Getting a Transplant

How do I start the process of getting a kidney transplant?

How does the evaluation process work?

What does the operation involve?

What are anti-rejection medicines?

After Your Transplant

What happens after I go home?

What if my body tries to reject the new kidney?

How often do rejection episodes happen?

Finding a Kidney

Where do donated kidneys come from?

Is it better to get a kidney from a living donor?

Are there disadvantages to living donation?

Transplant Basics

Considering and Preparing for a Kidney Transplant

- Getting Ready for a Kidney Transplant

- Preemptive Transplant

- Evaluation for Kidney Transplant

- Multiple Listing

- The Organ and Tissue Donor Program

- Antibodies and Transplantation 101

- Kidney-Pancreas Transplant

- 10 Things I Wish I Had Known Before My Transplant

- Pregnancy and Transplant

- Dental Health and Transplant

Table of Contents

- Kidney transplant & COVID-19

- What is a kidney transplant?

- What is a “preemptive” or “early” transplant?

- Who can get a kidney transplant?

- What if I’m older or have other health problems?

- How will I pay for a transplant?

- Getting a Transplant

- After Your Transplant

- Finding a Kidney

When your kidneys fail, treatment is needed to replace the work your own kidneys can no longer do. There are two types of treatment for kidney failure: dialysis or transplant. Many people feel that a kidney transplant offers more freedom and a better quality of life than dialysis. In making a decision about whether this is the best treatment for you, you may find it helpful to talk to people who already have a kidney transplant. You also need to speak to your doctor, nurse and family members

Kidney Stones

Table of Contents

- How common are kidney stones?

- What is a kidney stone?

- Causes of kidney stones

- Types of kidney stones

- Kidney stone symptoms

- Kidney stone treatment

- I think I have a stone. What do I do?

- Kidney stone diagnosis

- Why do doctors examine the contents of the stone?

- Long term consequences of kidney stones

- Reducing kidney stone risk

- Can children get kidney stones?

Each year, more than half a million people go to emergency rooms for kidney stone problems. It is estimated that one in ten people will have a kidney stone at some time in their lives.

The prevalence of kidney stones in the United States increased from 3.8% in the late 1970s to 8.8% in the late 2000s. The prevalence of kidney stones was 10% during 2013–2014. The risk of kidney stones is about 11% in men and 9% in women. Other diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity may increase the risk for kidney stones.

What is a kidney stone?

A kidney stone is a hard object that is made from chemicals in the urine. There are four types of kidney stones: calcium oxalate, uric acid, struvite, and cystine. A kidney stone may be treated with shockwave lithotripsy, uteroscopy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy or nephrolithotripsy. Common symptoms include severe pain in lower back, blood in your urine, nausea, vomiting, fever and chills, or urine that smells bad or looks cloudy.

Urine has various wastes dissolved in it. When there is too much waste in too little liquid, crystals begin to form. The crystals attract other elements and join together to form a solid that will get larger unless it is passed out of the body with the urine. Usually, these chemicals are eliminated in the urine by the body’s master chemist: the kidney. In most people, having enough liquid washes them out or other chemicals in urine stop a stone from forming. The stone-forming chemicals are calcium, oxalate, urate, cystine, xanthine, and phosphate.

After it is formed, the stone may stay in the kidney or travel down the urinary tract into the ureter. Sometimes, tiny stones move out of the body in the urine without causing too much pain. But stones that don’t move may cause a back-up of urine in the kidney, ureter, the bladder, or the urethra. This is what causes the pain.

Causes of kidney stones

Possible causes include drinking too little water, exercise (too much or too little), obesity, weight loss surgery, or eating food with too much salt or sugar. Infections and family history might be important in some people. Eating too much fructose correlates with increasing risk of developing a kidney stone. Fructose can be found in table sugar and high fructose corn syrup.

Types of kidney stones

-

There are four main types of stones:

- Calcium oxalate: The most common type of kidney stone which is created when calcium combines with oxalate in the urine. Inadequate calcium and fluid intake, as well other conditions, may contribute to their formation.

- Uric acid: This is another common type of kidney stone. Foods such as organ meats and shellfish have high concentrations of a natural chemical compound known as purines. High purine intake leads to a higher production of monosodium urate, which, under the right conditions, may form stones in the kidneys. The formation of these types of stones tends to run in families.

- Struvite: These stones are less common and are caused by infections in the upper urinary tract.

- Cystine: These stones are rare and tend to run in families. What are Cystine Stones?

Kidney stone symptoms

Some kidney stones are as small as a grain of sand. Others are as large as a pebble. A few are as large as a golf ball! As a general rule, the larger the stone, the more noticeable are the symptoms.

The symptoms could be one or more of the following:

- severe pain on either side of your lower back

- more vague pain or stomach ache that doesn’t go away

- blood in the urine

- nausea or vomiting

- fever and chills

- urine that smells bad or looks cloudy

The kidney stone starts to hurt when it causes irritation or blockage. This builds rapidly to extreme pain. In most cases, kidney stones pass without causing damage-but usually not without causing a lot of pain. Pain relievers may be the only treatment needed for small stones. Other treatment may be needed, especially for those stones that cause lasting symptoms or other complications. In severe cases, however, surgery may be required.

Kidney stone treatment

The treatment for kidney stones is similar in children and adults. You may be asked to drink a lot of water. Doctors try to let the stone pass without surgery. You may also get medication to help make your urine less acid. But if it is too large, or if it blocks the flow of urine, or if there is a sign of infection, it is removed with surgery.

Shock-wave lithotripsy is a noninvasive procedure that uses high-energy sound waves to blast the stones into fragments that are then more easily passed out in the urine. In ureteroscopy, an endoscope is inserted through the ureter to retrieve or obliterate the stone. Rarely, for very large or complicated stones, doctors will use percutaneous nephrolithotomy/nephrolithotripsy.

I think I have a stone. What do I do?

See a doctor as soon as possible. You may be asked to drink extra fluid in an attempt to flush out the stone out in the urine. If you strain your urine and can save a piece of the stone that has passed, bring it to your doctor. Or, the stone may need to be removed with surgery.

Kidney stone diagnosis

Diagnosis of a kidney stone starts with a medical history, physical examination, and imaging tests. Your doctors will want to know the exact size and shape of the kidney stones. This can be done with a high resolution CT scan from the kidneys down to the bladder or an x-ray called a “KUB x-ray” (kidney-ureter-bladder x-ray) which will show the size of the stone and its position. The KUB x-ray is often obtained by the surgeons to determine if the stone is suitable for shock wave treatment. The KUB test may be used to monitor your stone before and after treatment, but the CT scan is usually preferred for diagnosis. In some people, doctors will also order an intravenous pyelogram or lVP, a special type of X- ray of the urinary system that is taken after injecting a dye.

Second, your doctors will decide how to treat your stone. The health of your kidneys will be evaluated by blood tests and urine tests. Your overall health, and the size and location of your stone will be considered.

Later, your doctor will want to find the cause of the stone. The stone will be analyzed after it comes out of your body, and your doctor will test your blood for calcium, phosphorus and uric acid. The doctor may also ask that you collect your urine for 24 hours to test for calcium and uric acid.

Why do doctors examine the contents of the stone?

- There are four types of stones. Studying the stone can help understand why you have it and how to reduce the risk of further stones. The most common type of stone contains calcium. Calcium is a normal part of a healthy diet. The kidney usually removes extra calcium that the body doesn’t need. Often people with stones keep too much calcium. This calcium combines with waste products like oxalate to form a stone. The most common combination is called calcium oxalate.Less common types of stones are: Infection-related stones, containing magnesium and ammonia called struvite stones and stones formed from monosodium urate crystals, called uric acid stones, which might be related to obesity and dietary factors. The rarest type of stone is a cvstine stone that tends to run in families.

Long term consequences of kidney stones

- Kidney stones increase the risk of developing chronic kidney disease. lf you have had one stone, you are at increased risk of having another stone. Those who have developed one stone are at approximately 50% risk for developing another within 5 to 7 years.

Reducing kidney stone risk

- Drinking enough fluid will help keep your urine less concentrated with waste products. Darker urine is more concentrated, so your urine should appear very light yellow to clear if you are well hydrated. Most of the fluid you drink should be water. Most people should drink more than 12 glasses of water a day. Speak with a healthcare professional about the right amount of water that’s best for you. Water is better than soda, sports drinks or coffee/tea. lf you exercise or if it is hot outside, you should drink more. Sugar and high-fructose corn syrup should be limited to small quantities.Eat more fruits and vegetables, which make the urine less acid. When the urine is less acid, then stones may be less able to form. Animal protein produces urine that has more acid, which can then increase your risk for kidney stones.You can reduce excess salt in your diet. What foods are high in salt? Everyone thinks of salty potato chips and French fries. Those should be rarely eaten. There are other products that are salty: sandwich meats, canned soups, packaged meals, and even sports drinks.You want to try to get to a normal weight if you are overweight. But, high-protein weight loss diets that include high amounts of animal-based protein, as well as crash diets can add to the risk of stone formation. You need adequate protein, but it needs to be part of a balanced diet. Seek guidance from a registered dietitian when embarking on a weight loss diet or any dietary interventions to reduce the risk of kidney stones.Don’t be confused about having a “calcium” stone. Dairy products have calcium, but they actually help prevent stones, because calcium binds with oxalate before it gets into the kidneys. People with the lowest dietary calcium intake have an increased risk of kidney stones. A stone can form from salt, the waste products of protein, and potassium. The most common type of kidney stone is a calcium oxalate stone. Most kidney stones are formed when oxalate, a by product of certain foods, binds to calcium as urine is being made by the kidneys. Both oxalate and calcium are increased when the body doesn’t have enough fluids and also has too much salt. Based on blood and urine tests, your doctor will determine which types of dietary changes are needed in your particular case.Some herbal substances are promoted as helping prevent stones. You should know that there is insufficient published medical evidence to support the use of any herb or supplement in preventing stones.See your doctor and/or a registered dietitian about making diet changes if you have had a stone or think you could be at increased risk for getting a kidney stone. To guide you, they need to know your medical history and the food you eat. Here are some questions you might ask:

- What food may cause a kidney stone?

- Should l take vitamin and mineral supplements?

- What beverages are good choices for me?

Can children get kidney stones?

- Kidney stones are found in children as young as 5 years. In fact, this problem is so common in children that some hospitals conduct ‘stone’ clinics for pediatric patients. The increase in the United States has been attributed to several factors, mostly related to food choices. The two most important reasons are not drinking enough fluids and eating foods that are high in salt. Kids should eat less salty potato chips and French fries. There are other salty foods: sandwich meats, canned soups, packaged meals, and even some sports drinks. Sodas and other sweetened beverages can also increase the risk of stones if they contain high fructose corn syrup.

Nutrition and Kidney Disease, Stages 1-4

-

- Nutrition and Chronic Kidney Disease

- Nutrition for Children with Chronic Kidney Disease

- Good Nutrition for Chronic Kidney Disease

Most patients in the early stages of kidney disease need to limit the amount of sodium in their diet. Some patients may be told to limit protein in their diet as well. The DASH diet is often recommended for patients with kidney disease. Be sure to talk with your healthcare provider about your specific nutrition needs.

- DASH Diet

- Plant-Based Diets

- Enjoy Your Own Recipes Using Less Protein

- Sodium and Your CKD Diet: How to Spice Up Your Cooking

If your kidney disease gets worse, you may also need to limit potassium or phosphorus in your diet. Talk with your healthcare provider about your specific nutrition needs.

Here are some additional resources to help you stay healthy with kidney disease through your diet:

- Your Diet and Kidney Health: Managing Protein

- Protein – Variety and Moderation is the Key

- Carbohydrate Counting with Chronic Kidney Disease

- How to Increase Calories in Your CKD Diet

- Cholesterol and Chronic Kidney Disease

- Dining Out With Confidence

- Use of Herbal Supplements in Kidney Disease

- Vitamins and Minerals in Kidney Disease

- What You Should Know About Good Nutrition

- Your Guide to the New Food Label

- Spice Up Your Diet

- Food Safety is a Must!

- Cookbooks for Kidney Patients

- Dairy and Our Kidneys

"Causes of Frequent Urination"

Diabetes. Frequent urination with an abnormally large amount of urine is often an early symptom of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes as the body tries to rid itself of unused glucose through the urine.

- Excessive thirst

- Stomach upset

- Nausea and vomiting

- Constipation

- Bone and muscle pain and weakness

- Brain issues: Confusion, fatigue, and depression

- Heart issues (rare): Racing or skipping pulse (arrhythmia) and other heart problems

Diagnosing the Cause of Frequent Urination

If urinary frequency interferes with your lifestyle or is accompanied by other symptoms such as fever, back or side pain, vomiting, chills, increased appetite or thirst, fatigue, bloody or cloudy urine, or a discharge from the penis or vagina, it’s important to see your doctor.

- Are you taking any medications?

- Are you experiencing other symptoms?

- Do you have the problem only during the day or also at night?

- Are you drinking more than usual?

- Is your urine darker or lighter than usual?

- Do you drink alcohol or caffeinated beverages?

Depending on the findings of the physical exam and medical history, your doctor may order tests, including:

Blood Tests. Routine blood test can check for kidney function, electrolytes, and blood sugars

Urinalysis. The microscopic examination of urine that also involves a number of tests to detect and measure various compounds that pass through the urine.

Cystometry. A test that measures the pressure inside of the bladder to see how well the bladder is working; cystometry is done to determine if a muscle or nerve problem may be causing problems with how well the bladder holds or releases urine. There’s a broader term called urodynamics that includes tests such as cystometry, uroflowmetry, urethral pressure and others.

Treatment for Frequent Urination

Treatment for frequent urination will address the underlying problem that is causing it. For example, if diabetes is the cause, treatment will involve keeping blood sugar levels under control.

The treatment for overactive bladder should begin with behavioral therapies, such as:

- Bladder retraining. This involves increasing the intervals between using the bathroom over the course of about 12 weeks. This helps retrain your bladder to hold urine longer and to urinate less frequently.

- Diet modification. You should avoid any food that appears to irritate your bladder or acts as a diuretic. These may include caffeine, alcohol, carbonated drinks, tomato-based products, chocolate, artificial sweeteners, and spicy foods. It’s also important to eat high-fiber foods, because constipation may worsen the symptoms of overactive bladder syndrome.

- Monitoring fluid food intake. You should drink enough to prevent constipation and over-concentration of urine. Avoid drinking just before bedtime, which can lead to nighttime urination.

- Kegel exercises. These exercises help strengthen the muscles around the bladder and urethra to improve bladder control and reduce urinary urgency and frequency. Exercising pelvic muscles for five minutes three times a day can make a difference in bladder control.

- Biofeedback. This technique can help you learn how your pelvic muscles work to help you better control them.

Treatment may also include drugs such as darifenacin (Enablex), desmopressin acetate (Noctiva), imipramine (Tofranil), mirabegron (Myrbetriq), oxybutynin (Ditropan), oxybutynin skin patch (Oxytrol), solifenacin (Vesicare), tolterodine extended-release (Detrol LA), and trospium extended-release (Sanctura XR). Oxytrol for women is the only drug available over the counter. Darifenacin is specifically for people who wake up more than twice a night to urinate.

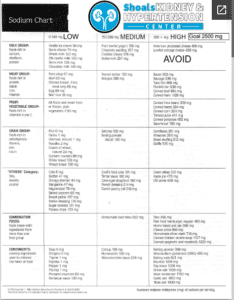

Reduce Sodium

There are many herbs and spices that you can use to add flavor to your food instead of salt. Also, certain foods have more sodium than others. See the following table for some suggestions on how to reduce sodium in your diet:

| Limit the Amount of… | Food to Limit Because of their High Sodium Content | Acceptable Substitutes |

|---|---|---|

| Salt & Salt Seasonings |

|

Fresh garlic, fresh onion, garlic powder, onion powder, black pepper, lemon juice, low- sodium/salt-free seasoning blends, vinegar |

| Salty Foods | High Sodium Sauces such as:

Salted Snacks such as:

|

Homemade or low-sodium sauces and salad dressings; vinegar; dry mustard; unsalted crackers, popcorn, pretzels, tortilla, or corn chips |

| Cured Foods |

|

Fresh beef, veal, pork, poultry, fish, eggs |

| Luncheon Meats |

|

Low-salt deli meats (if you need to limit phosphorus, these are likely high in phosphorus) |

| Processed Foods |

Canned:

Convenience Foods such as:

|

Natural cheese (1-2 oz per week)

Homemade or reduced-sodium soups, canned food without added salt

Homemade casseroles without added salt, made with fresh or raw vegetables, fresh meat, rice, pasta, or no added salt canned vegetables

|

Why do I need to limit my sodium intake?

Some salt or sodium is needed for body water balance. But when your kidneys lose the ability to control sodium and water balance, you may experience the following:

- thirst

- fluid gain

- high blood pressure

- discomfort during dialysis

By using less sodium in your diet, you can control these problems.

Hints to keep your sodium intake down

- Cook with herbs and spices instead of salt. (Refer to “Spice Up Your Cooking” section for further suggestions.)

- Read food labels and choose those foods low in sodium.

- If you need to limit potassium avoid salt substitutes (such as potassium chloride) and specialty low-sodium foods made with salt substitutes because they are high in potassium.

- When eating out, ask for foods prepared without salt. Ask for gravy or sauce on the side; these may contain large amounts of salt and should be used in small amounts.

- Limit use of canned, processed, and frozen foods.

Some information about reading labels

- Understanding the terms:

- Sodium Free – Only a trivial amount of sodium per serving.

- Very Low Sodium – 35 mg or less per serving.

- Low Sodium – 140 mg or less per serving.

- Reduced Sodium – Foods in which the level of sodium is reduced by 25%.

- Light or Lite in Sodium – Foods in which the sodium is reduced by at least 50%.

- Simple rule of thumb: If salt is listed in the first five ingredients, the item is probably too high in sodium to use.

All food Nutrition Facts labels have milligrams (mg) of sodium listed. Follow these steps when reading the sodium information on the label:

- Know how much sodium you are allowed each day. Remember that there are 1000 milligrams (mg) in 1 gram. For example, if your diet prescription is 2.3 grams of sodium, your limit is 2300 milligrams per day. Consider the sodium value of other foods you plan to eat during the day.

- Look at the package label. Check the serving size. Nutrition values are expressed per serving. How does this compare to your total daily allowance? In general, the item is not a good choice if:

- The sodium level is 240 mg or more per serving, the item is not a good choice.

- The milligrams of sodium are greater than the calories per serving

- Compare labels of similar products. Select the lowest sodium level for the same serving size.

Dashplan_24 pdf

Low Sodium Diet pdf

Dash_Brief pdf